Letter 1

Letter 1

The enduring image one has of the Island of Bali - the Island of the Gods - is of men squatting beside the road stroking their cocks. Fortunes are won and lost on a six-second flurry of feathers and steel-bladed spurs, In the rest of the Indonesian archipelago cockfighting has been banned; but not in Bali, It is part of the ritual of the many thousands of Hindu temples which cover the island and the Balinese adamantly refuse to give it up. In this country, until recently ruled from Jakarta by a military dictatorship, it is rare for the Government to give way. But in the matter of the Balinese and cockfighting their options were few.

It is said of ceremonies that 'work' is the thing which occupies the space between them. Every village has at least three temples and every temple has two major ceremonies a year and often one minor ceremony every full moon. Not counting weddings tooth-filings, funerals, cremations and special days for certain Deities this adds up to a formidable number. And an Odalan ( a ceremony) is not some shuffling Parish Communion attended by only a few elderly or die-hard Hindus, it is a three-day event (with as many days before it to prepare) which is morally obligatory for every villager, senile or infant. And who would not attend? Feasting and dancing, music and puppet shows, gambling and cockfighting, market stalls and soothsayers collocate themselves round the temple compound and spill out into the road beyond. You can tell when a village has an Odalan. Throughout the day small processional groups of women file to and from the temple. They are dressed in their temple clothes: a lace blouse always in some vivid, primary colour, their best and most colourful sarongs, their black hair is tied up in a bun and bedecked with flowers. On their heads they balance their offerings to the gods: towering creations of fruit, flowers - even roasted chickens - arranged with such artistry on a chased silver dish. Unaided by any guiding hand the women thread their way through traffic bearing these offerings - some two, or even three feet high - and I've never seen one topple over. The men have been up since 4 a.m. killing and cleaning pigs for spit-roasting. Now they sit around in their temple clothes: immaculate white shirt and sarong overtopped with another gold apron. On their heads an udung , a white scarf folded and knotted intricately to form a tight-fitting cap. A frangipani flower behind one ear, a little make-up and stars of white rice at the edge of the eyes after they have prayed adds the finishing touches.

I am often invited to odalans. The noise, the smells, the crowds are terrific. All day, in the inner sanctum of the temple, family groups arrive to pray and be blessed by the Pidanda.. This 'High Priest' is a man of immense influence and gravitas to whom one turns for all advice: the right time to plant and harvest the rice, the most auspicious day to buy your new car or put a roof on your new house. In the quietude of this part of the temple, the men on one side, the women on the other, small bells tinkle intermittently, unison bows of deep veneration sound with a rustle of silk; a whispered prayer, a raising of mystical flowers above the lowered head; all turn to Mount Agung - that magic volcano which rises 10,000 feet in front of my house, and which is the home of the Gods. It's all over in a few minutes and groups of worshipers chat amongst themselves as they retreat from the inner sanctum. Outside in the courtyards all is riotous. You want to eat? Stalls sell all the traditional foods: the ubiquitous nasi goreng (fried rice - the fish and chips of Asia), mie goreng (fried noodles), bakso and tempe and of course sate - skewers of spiced fish, chicken, goat or pork barbecued over charcoal and dunked in a ravishing aromatic peanut sauce. Your for 2p a skewer. You want to but a shirt? or jeans? or knickers? or a new sarong ? Plastic toys for the children? Ten, twenty stalls are waiting to take your money. You want to make your penis larger? Or have more babies? There's a man over there with a potion for everything. You want to play dominoes, or gamble with dice or have your Tarot read? Here they are. And in the banjar - the community hall adjacent to the temple - the seats are ranged ready for tonight's performance. A play this time perhaps, or a ballet, or an opera, or Wayang Kulit - that unique shadow-puppet show beloved of all Balinese. Whatever it is, there will sit, patiently waiting at the side of the stage and behind their instruments, thirty or forty men, the pride and joy of every village, the Gong Gamelan.

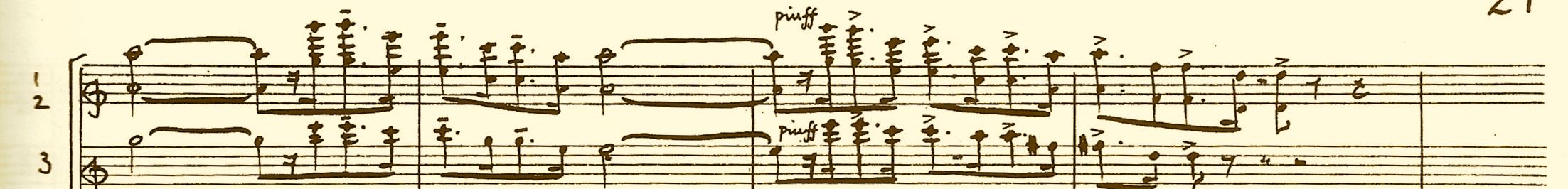

'Gong' is a Balinese word and means the same in English. 'Gamelan' means 'orchestra'. A whole orchestra of gongs. Not all are round and booming, some are small and like upturned bronze pots with a central knob; others are not gongs at all but bronze bars with bamboo resonators underneath - most like our xylophones or vibraphones. There are bamboo flutes too, and rebabs (two-stringed fiddles) and small cymbals and drums. Every westerner on first hearing a Balinese gamelan is thunderstruck - not just by the racket but by the speed and complexity of the music. Every moment is carefully and meticulously rehearsed; not even the immensely difficult drum rhythms are improvised. Nothing is written down but learned by rote and a ballet or drama gong ( a play with music) starts at around 10 p.m. and may not finish until four or five in the morning; six or seven hours of continuous playing.

After eight years I still haven’t got to grips with the extraordinary magnitude of the creativity of all kinds which goes on here. Every other person does something creative: dancers, musicians, writers, poets, painters, woodcarvers, stone sculptors, potters - they’re all at it in some way or another. Few would describe their activity as ‘professional’. Only those who market to the tourist trade make a living out of their creations - and even then it is often considered a part-time occupation which fills in the time between planting and reaping - and, of course, temple ceremonies. To watch a couple of boys, maybe no more than ten years old, fashion the most stunning kite out of a few old plastic bags and some bits of bamboo they’ve picked up on the way home from school, is salutary. They simply can’t help but make it beautiful. In any household the girls of whatever age will help make the daily offerings; intricately woven trays of palm-frond, flower petals and leaves pinned together by the hard, central leaf-stems of a certain kind of palm. It is the Balinese equivalent of origami. But they are made by tiny children! We wouldn't let our tots near the knife, let alone expect them to cut the quarters of an abstract pattern.

It would be an error to think that all this creativity is in some way like our own pursuit of hobbies. It is not to be thought of as the Hindu equivalent of corn dollies or hassock tapestry making. Our gamelan group practises hard; there’s no two ways about it; much harder than an amateur choral society in the West. If there is an important function coming up, we may rehearse as frequently as every other day. We have about thirty pieces in the repertoire - some lasting up to half-an-hour, or as long as a Mozart symphony - any one of which may be called upon at any time for weddings, cremations, blessings and temple ceremonies. All of them are memorised. Unless we are learning a new piece, most of a two-hour rehearsal is taken up by reviving certain pieces for the next performance. I am, needless to say, absolutely hopeless at it. I simply cannot remember so many notes by rote. I don’t get too depressed about this; after all, they can’t read music, but it is a humbling experience nonetheless. A quick play-through will jog their memory; one player will remind his neighbour how it goes. As we play, the drummers, who are also the teachers, are constantly keeping a keen ear on what’s going on around them. One of them might put his drum down and sit opposite a confused player and help him by playing with him in reverse. That is, on the other side of the instrument. Thus the teachers know all the dozen or so different parts of all the pieces backwards. Literally backwards. Do I know even my own music backwards? I cringe with embarrassment: no, I do not. It would be astonishing enough if the music they learn so thoroughly was ancient and traditional - in the blood, as it were - but we play contemporary music. One piece in our repertoire, Pengelong Jiwa ("The Spirit of Long Life"), was only composed last year.

In our group we have schoolboys, farmers and builders’ labourers. Pak Pasek, who is the secretary of the group, is the owner/driver of a minibus; Pak Minggu, one of our teachers, is a security guard. There are no ‘professional’ people in the group. Whether the newly emerging middle class thinks such activity is beneath them, I cannot say. But I doubt it. All Balinese are intensely interested and proud of their unique culture. There are endless debates in the local press and endless seminars in the universities on the topic of Balinese culture and tradition. These discussions generally revolve round the influence, for good or ill, of tourism on the island. Is Bali benefiting from cultural tourism, or is Bali a touristic culture? It is a complex issue. Many point to the way in which the adat, the tradition, is being at best changed and at worst eroded by the influence of millions of tourists who come here every year. Others point out that, were it not for the tourists, many of the gamelan groups, dancers, painters and so on simply would not survive.

What is true is that the development of tourism on Bali was not a decision made by the Balinese; it was imposed on them by their political masters in Jakarta. The Balinese had very little say in where and what kind of tourism would be encouraged in Bali and receive the necessary investment. Certain traditions, cockfighting and the more overtly salacious dances for instance, have even been actively discouraged because the politicians fear they might offend the tourists. I’m glad to say the Balinese hit back, and banned certain sacred dances and dramas from being used as mere entertainment by the tourism industry. It is a dilemma we ourselves have failed to address: would the choirs of Westminster Abbey or King’s College Cambridge exist in their present form were it not for tourists? Or do the tourists provide the means and the impetus by which the once-spiritual Choral Evensong can be maintained? This is the Balinese predicament: how do you know, unless, to find out the answer, you ban all tourists, cut no CD’s and turn in on yourselves?

It goes further than that. Certain dances were composed and choreographed in the 1970’s and 1980’s to be especially attractive to tourists. Whereas the ceremonial dances are long and abstract, these newly composed dances are short, narrative and easily digestible by those who do not understand the nuances of Balinese dance techniques. These dances have found their way into traditional ceremonies in villages right across the island, and are even described in tourist blurbs as ‘traditional’ Balinese dances. The Balinese themselves have now come to consider them as adat and few remember they are recent and wholly foreign to temple ceremonies. Having been originally designed for a very specific purpose, they have quickly become, like the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, part of the general sacred tradition without anyone really realising it.

For me it is magical to walk through the terraced padi-fields by the brightest moonlight I have ever encountered and with only the frogs to disturb the stillness. Then, round a corner, the distant tinkling and boom of a gamelan rehearsing. I call forward to Yudhi whose perfectly balanced footfalls guide us on the narrow pathways curling round the terraces. "Is that coming from Penestanan or Sayan?"

"Penestanan I think."

"Let's go and look!"

Between two compounds we emerge into the main street of the village. It is dead straight, running north to south and fringed by storm drains and flowering trees and shrubs. Dim bulbs offer a minimum glow and welcome from every arched gateway. There in the banjar at the north end of the street sits the gamelan. "Selamat Malam, Robett! Selamat Malam Ida Bagus!" "Good Evening.....Selamat Malam." Greetings by the light of hard-white neon slung precariously from the rafters.

We squat at the side of the pavilion and listen. Mallets fly hither and yon and some of the boys smile at us and wink. One of them beckons for a cigarette, and without breaking his rhythm lights up with his free hand. Suddenly the music stops. "Tidak!" The drummer (who is usually the leader and often the composer) calls out. "Ding-dang-deng-dong-dung." He sings in their version of tonic-solfa (soh-me-fah-ti-doh), and faces the offending player across his instrument. (Try playing even a child's xylophone back-to-front!) While he demonstrates the correct pattern the rest set up an ear-splitting cacophony of metal as they too practise difficult moments. There are smiles of private accomplishment or sheepish grins of imperfection to sympathetic neighbours. At a signal - the flick of a mallet - the music begins again: a metallic crash of all the instruments, then fleeting solos. Soon the rhythm is in place and cascades of glass fill the spatial air. The intermittent boom of the great gong reaches into the marrow; the drums beat primordial messages into long-forgotten recesses of the mind. It is all-embracing on every level, and thought cannot compete.