I Miss Saigon -Postcard from VietNam

In 1960, 25 years after the Second World War, I was a 14 year old schoolboy. There were still some traces of that war; bombed-out churches mostly, but skeletal factories too, cracked pavements and bullet holes still visible in soft Portland stone. But generally speaking not much to show for six years of horrendous bombing. Resurrection really, encapsulated by the soon-to-be consecrated, new Coventry Cathedral.

So why was I surprised to find not a trace anywhere of the thirty years of war the Vietnamese waged first against the French and then against each other - North and South - with a little help from The United Sates, Australia, Russia and China? The war ended only 25 years ago and I was expecting a ruined city as we flew into Saigon, but there were no bunkers, nor bomb-sites, no wastelands nor craters. The carpet-bombing had been shampooed away, agent orange had been flushed down the drain, and there was no sign anywhere (at first) which told of those horrific decades of mayhem.

Except in a name. Saigon, epitome of everything decadent, sleazy, raunchy and Western has been renamed Ho Chi Minh City and has been forced to mend its ways to suit its eponymous hero; the unblemished founding father of modern Vietnam was nothing if not upright and virtuous. The name Saigon still exists as the downtown District 1 of the much larger conurbation of HCMC (as it is known by almost everyone) and it is where we pitched our tent.

At first, as we travelled into the city from the airport, HCMC seemed like any other Asian city; concrete shop-houses and chaotic traffic. But I noticed how well painted all the buildings were. In Bangkok, Manila or Jakarta the heavy rains and little or no maintenance have turned their concrete buildings black and squalid; but not in Saigon. Here all the buildings were well maintained and painted in most attractive hues of brown, red and yellow ochre. Then, out of the blue, appeared the first green-shuttered French villa (....;and a French widow in every room'...) and then the first, tree-lined boulevard. We were in Paris! An Art Deco café announced 'Patisserie et Boulangerie' in that type-face unique to Parisian café society, and young Vietnamese sat out on cane chairs in front sipping a small espresso; an elderly, maroon, beautifully restored Maigret Citröen passed us in the street; conduit water ran down the gutters of the central district to sluice away the day's debris just as it does in Paris; and at the end of the widest and longest boulevard of all sat the yellow and white painted Hotel de Ville, for all the world as though it had been plonked there from some Provençale town. Caryatids supported the clock, and - possibly unique in Asia - it told the correct time. The French built their colonies with great style. Who could have possibly imagined this beautiful city would have risen again out of one of the worst conflicts of the twentieth century? Every building has been lovingly restored, as they have in Prague and Leipzig. No Coventry city centre here! No wind-swept, rusty shopping 'Piazza' in Plymouth! Oh! Blessed war! Oh! Blessed Americans who, mealy-mouthed and bad losers, never paid war reparations - as most losing sides are forced to do! With no money to tear down old buildings and construct shopping Malls and office blocks, the city's administrators had done the next best thing and rebuilt what was already there. It's better than that: realising they had a most wonderful architectural heritage, they have insisted (or at least encouraged) that new buildings should reflect the old styles. There is a new department store going up just along the road from our hotel. It looks like Printemps. And, for the moment at least, there is not one Macdonald's in the whole of Ho Chi Minh City. (There is a Kentucky Fried Chicken however, but it is discreetly and thankfully tucked away at the top of a department store...)

On our first evening we sat out of the pavement outside Highlands Café and sipped delicious Vietnamese iced black coffee. In front of us was a huge square with the cathedral of Notre Dame in the middle of it. Romanesque and built of brick, its two spires were still the dominant feature of downtown Saigon and traffic whirled round them. We used these spires frequently to orient ourselves when traversing on our hired motorbike the grid of boulevards which the French had built more than a century ago. ("Look! There's the cathedral spires so we need to turn left at the next junction...") On the north side of the square stood the most beautiful building of all: the General Post Office. Floodlit pale yellow Classical stucco fronted a cavernous interior of intricately painted cast-iron columns supporting a vaulted roof. The floor was patterned with multi-coloured encaustic tiles, and (gratefully for this foot-sore tourist) heavy Mahogany benches, arranged in rows, ensured a comfortable sojourn if the queues were long. Only circling fans and a huge picture of Uncle Ho dominating the far end told you this was not a tidy Gare du Nord without the trains.

If you have a Vietnamese restaurant near you and haven't tried it, I urge you to do so. Vietnamese cuisine is delicious. Not as fiery as Thai dishes and not as boringly bland as Indonesian, it combines the best of both with a touch of French haute cuisine thrown in. We ate on our first night and frequently thereafter at Pacific restaurant a few metres from our hotel. It's a micro-brewery (we were to discover there were quite a few of these) where they brew their own beer and serve it to you unbidden whether you like it or not. (One waiter's only job was to pass glass after glass under a continuously running tap of frothing beer to pass to other waiters who carried them off to whomsoever wanted yet another half-litre.) It was very basic. We sat at tin tables on plastic stools under a tarpaulin. Less-than-effective Hitachi fans bowed gracefully from side to side but were no match for the crowds of locals who ate there. The heat was terrific and not helped by the speciality of the house, a hot pot of spiced and herbed broth brought to your table on a portable gas stove in which one dunked slivers of raw beef, pork, chicken, prawns, oysters, clams, squid and green vegetables to taste.

One of my greatest surprises was the bread. I long since had given up any idea of ever eating proper farinaceous fare in Asia; it's all steam baked, soft, tasteless and sometimes verdantly green. But the French had not stopped at building roads and post offices. Brioche, croissant and baguettes of every description were tumbling out of bakeries on every other corner. Cake shops were more common in Saigon than pubs in London. Wheat doesn't grow in the tropics so where do they get the flour from? They must import it by the tanker-load and pay in very hard-earned dollars. Their friends in the Soviet Union are no longer in control, but perhaps old wheat roads, like old silk roads, just keep on running. More understandable, but no less delicious was the coffee. In the main covered market huge glass-sided canisters held Robusta, Arabica, Mocha, Blue Mountain and all stations to Espresso. A fiver or less will get you a kilo.

We toured most of the sights in Saigon, but the one which stays indelibly in my memory was the 'Museum of War Remnants'. Old American tanks, Howitzers and war-planes stood sadly and unthreateningly in the forecourt. Huge bombs, dropped from B 52s, stood on the ground pointing upwards to the sky. No mention was made, of course, of the wickednesses perpetrated by the North Vietnamese - they were the victors after all, and only the vanquished have their dirty linen washed in public. In a series of rooms we learned of the 'heroic struggle' of the Vietnamese people against their three oppressors: the French, the Japanese, the French again and finally the Americans and her satrap allies. It made grim viewing. A video showed in all its horror the effects of napalm and agent orange on children and the unborn. I'm not a little squeamish, and on more than one occasion had to avert my face and think hard about something else. In another building was a genuine guillotine, last used by the French colonialists in 1960. It was remarkably small and not as tall as I had always imagined a guillotine would be. I wondered if the gravitational force was unerringly sufficient for the descending blade (now rusty and distinctly blunt) to ensure a clean chop every time. If it wasn't, the consequences were too ghastly to contemplate. Nobody ever mentions these things, do they? Further on in the same building was a mock-up of a torture chamber and the cages in which the victims were incarcerated. Graphic coloured drawings spared us no details of how it was all done. My head began to swim and I felt nauseous. "I'm going outside to get some air." I said to Walt. "I can't take much more of this."

And what was all this hideous suffering for? What evil devils did the Americans think the Viet Cong were? From what were they 'saving' these hard-working, gentle, kindly Buddhists? As the Americans are even now preparing for another innings of their game of 'save the world' - this time against Iraq - is it not timely to remind them that even when they don't succeed the results are not as they imagined. Walk right outside the 'Museum of War Remnants' and you see a beautiful, bustling town going about its business like any other. There is no Orwellian nightmare except in the imagination. No-one looks oppressed, no-one is in shackles. We rarely saw policemen on Saigon's streets and certainly fewer than stand menacingly in Bangkok or New York. Vietnamese cities are not even bleak, as Soviet cities were. Yes: it's a one party state. But so what? What makes the addition of a second party so essential that millions of people should die or walk for the rest of their lives on crutches? I am not advocating Communism, I am advocating non-involvement in other countries' affairs, except where there is clear evidence of evil intent, as there is in Burma which the Saviours of the World studiously ignore. Was there any evidence that Ho Chi Minh was evil? And even if Saddam Hussein has evil intent, is there no other way than to bomb the bus-driving, library-ticketing, house-hunting, report-writing Iraqis and their children into oblivion? One caption in the museum quoted an American general: "To save them we just had to bomb their village". I really don't want you to laugh at this. It's not funny. If you have the means, please send some Iraqi teenagers to Vietnam and say "Look! Don't be afraid. Just keep your head down. It will pass."

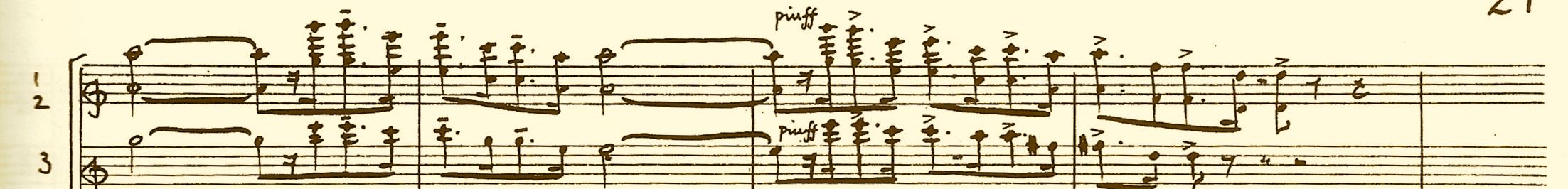

I had letters of introduction to a number of musicians and my first visit was to Mr. Than, the conductor of the HCMC Symphony Orchestra. Mr Than is also a composer and we had a happy couple of hours gassing away. No-one is well paid in Vietnam, not even conductors of symphony orchestras, and I felt only sympathy for him as he struggled with the exorbitant cost of orchestral scores and music books in a run-down house with no air-conditioning. As his wife silently brought us green tea, I mentioned I was writing a piece for double string orchestra. "Please send it to me via e-mail!" He declared. "I can run off the parts easily and we will play it!" And I will. This seems to me to be the way music will be propagated in the future. Music Publishers know nothing of the struggle artists have in developing countries, and care even less. They have had it too easy for too long and the writing is on the wall for them.

Mr. Than invited me to the Conservatory of Music that evening where there was to be a concert given by a French Baroque ensemble sponsored by the French Embassy. (Since the days of Mrs. Thatcher, the British Council has abandoned all attempts to be a cultural ambassador for British creative artists, and I note with regret that Mr. Blair's government has never sought to reverse that policy. So much for 'Cool Britannia'!)

The conservatory (Why are they called that? What do we 'conserve'?) was wonderful. The art-deco concert hall was large and plush and with marvellous acoustics. The hall sat in the middle of a square of buildings with the road taking up the fourth side. The three teaching buildings had wide galleries round each of four floors with practice rooms and lecture halls running off them. The ensemble of all these art-deco buildings was very pleasing, so I was astonished to learn that the Vietnamese government had only begun building them in 1994. This academy for musicians was not a French legacy, as I had first thought, but a completely new enterprise. I was even more astonished to observe later each practice room and teaching room had a new Yamaha grand piano in every room. Here 1500 students from six years of age to doctorates learned their craft. And it is all free. When there was so much reconstruction to do - so many roads to repair, so many bridges to reconstruct - it was sobering to realise the government thought a conservatory of music was a high priority. This, dear reader, was what the Americans had tried to prevent. As I sat listening to Vivaldi played on authentic instruments to a packed audience in the middle of Saigon, I wondered, had the South Vietnamese won the war, whether this concert hall and this concert would have been there at all. Unlikely. There would have been flyovers, fast-food joints and MTV covering the whole city long before anyone would have considered it. Who, I mused, are the civilised and who are the vandals? (And just in case my British readers might smirk in knowing presumption, I should inform them that the first university in Vietnam was founded in 1024 A.D. - 200 years before Oxford and Cambridge.)

At the concert I was introduced to the director of the conservatory, Mr. Choang. He keenly invited me to call on him the next day. English composers don't often pass through Saigon. Posters on his study wall proclaimed him to be a violinist of some distinction and a former student of the Liszt Academy in Budapest and the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in St. Petersburg. The Soviet bloc, of course, was where the Vietnamese, on generous scholarships, had gained their only first-hand experience of European culture. They knew nothing of Vaughan Williams, Elgar or Tippett - or Copland and Percy Grainger for that matter - but had under their finger tips every Russian composer from Arensky to Zemlinsky. The West lost more than just a war.

Hanoi was even more wonderful than Saigon. The Old Quarter was a warren of narrow streets, each one of which specialised in one product; a whole street of shops selling tin boxes, or children's toys piles in great pyramids up to the first floor and hanging from the trees in front, or a street - quite long - in which there was nothing but travel agents. This is the Chinese merchants' way and we have something like it in China Town in Bangkok, but I've never really understood the economics of it. Each shop sells exactly the same thing at roughly the same price (because they can easily hear what Mr. Chan next door and Mrs. Quin over-the-road is bargaining down to). There is simply no competition either for price or location. It is awkward for the consumer too. If you live in the suburbs of Hanoi and want to buy your daughter a doll, you have no choice but to travel into the centre of the city. But the streets themselves were simply charming: old shop-houses, beautifully restored with up-curling Chinese roof-tiles, the walls painted yellow and with green shutters, hid behind Acacia trees which shaded the road below.

I was in Hanoi only a short time so took a rickshaw for an hour (here called 'cyclos') and asked the rickshaw pedaller to take me round the sights. The large area which constitutes the centre of Hanoi is dotted with lakes and parks. The French, too, had done their bit. Long vistas down wide boulevards led to the famous (and very beautiful) Hanoi Opera House. Next to it was the real, newly built Hanoi Hilton, looking for all the world as though it had been a left over from the plans for the Royal Crescent in Bath. (You will remember, if you are old enough, 'The Hanoi Hilton' was what the GI's had dubbed the infamous gaol in which POW's were incarcerated and often tortured.) Only Ho Chi Minh's mausoleum jarred. Dominating a huge cobbled square it apes Mao Tse Dhong's mausoleum in Beijing; Communist glorification in heavy Greek architecture brazenly propagates a personality cult. Uncle Ho's body, apparently, has to go to Moscow periodically; the old Leninists there are the experts in preserving it. As the cyclo slowly circumnavigated the streets, we passed many cafés with the young and the trendily dressed sipping their drinks and gossiping animatedly in the cool evening air. Nothing about them was extraordinary except that 25 years ago they were clamping their ears and screaming at their mothers to please stop the bombs. Mummy, I don't want to play this game any more. Please make them stop. Hush, my child. It will pass.

My hotel was near one of the largest lakes in Hanoi so, after my cyclo tour, I walked down to the edge and sat on a bench to enjoy the breeze coming off the water. Almost immediately a young man came and sat beside me. He was very polite. "May I sit here? Do you mind if I talk with you?" Not at all. Not at all. His name was Guan and he came from a small village many hundreds of miles from Hanoi in the centre of this long, thin country. He had just finished a course in auto-mechanics and was now looking for a job but it was very difficult. Are there no jobs for auto-mechanics in your village? He scoffed. "Nobody has a car where I come from. We are all farmers." I pointed out his English was very good. Surely he should be able to use that skill for something? "But I like working with automobiles." I asked him how much he hoped to earn in his chosen trade. "It depends on how busy the garage is. If it's a good one and many wealthy people bring in the cars, I might be able to earn as much as $65." A day? That's good! I said, knowing how cheap everything had been on my journey. But as his face fell I could have bit my tongue. "No. A month." He said. I was incredulous. But surely you cannot live on that? "No. It's very difficult. Rent for a room is very expensive here in Hanoi. Most people have two jobs. I'll try to get a waiter's job too." Eventually our conversation got round to what he really wanted to talk about. He was, it turned out, gay and he told me about his life. "I had a girlfriend when I was in high school, but it never seemed right. Only when I came to Hanoi and had a friend in my class could I know who I was; what kind of man I was. We were very happy together, but of course we kept it secret from all our classmates." Were happy together? What happened to your boyfriend? "Oh! Last month he went back to his village to get married. We all have to get married." You too? I looked at him quizzically. "I suppose so." He said glumly. "It's expected here in Vietnam. But I shall not do it for a long time yet." Does your family ask why you are not married already? "No. Not yet. I am only 25. Too young to get married. But they will, and I must obey them." Times are changing, I said - to give his some encouragement, maybe they will accept you for what you are. They will still love you, just the same. "But they must have grandchildren." He said. "Who will look after them if something happens to me?" Not the Communist Party, evidently...

I was tired and made to excuse myself to go back to the hotel. "May I come with you?" He asked, as polite as ever. "May I walk with you back to your hotel? I am going that way." So we set off together and chatted amiably on the way. As we crossed the road in front of my hotel, he took my arm as if to guide me across and moved very close. "I have no room where to sleep tonight." He whispered. "And I have not eaten today." I slipped him him 50,000 Dong (about £2 or $3); surreptitiously, so no passing couples ambling in front of the now closing shops would see. "Go and eat." I said. It was worth it just to see the beam of gratitude light his face.