Three-and-a-half Concerts

It might be thought by some Metropoles that living in Asia, in Buddhist Thailand, especially in get-rich-quick Bangkok there would be little to sustain the European intellect or feed the spirit. This is, fortunately, not the case. In Kinokunya Bangkok possesses one of the best bookshops I know; it far surpasses the usual Waterstones (maybe because it has a music section which actually includes music) and perhaps is only rivalled by Hatchards. We get few art movies, but cinemas abound and most of the movies destined for general release find their way here eventually.

In music we have a superabundance, and I have just 'attended' three concerts in two days. (I put attended in quotes because I conducted one of them.) Not all of them are worth a second glance, but then neither are many held in London or Paris.

And so, on Thursday last, to The Art of Noise - a witty title given to a concert of contemporary music by some of my Thai colleagues in the College of Music, Mahidol University, but held (because our own auditorium is still not quite ready) at the Goethe Institut. The Goethe Institut, along with its sister The Alliance Française, provides a cheap, ideal venue for chamber recitals. The British Council has long since abandoned any attempt to portray itself as a centre for British culture and now only exists to make money by providing English language courses, and store rows and rows of brochures from British institutions of learning ("You'll get what you need at the Littlehampton School of English!"). I'm told it is very expensive and doesn't do either of these things as well as the Australians. The auditorium of the Goethe Institut is very like a Parish Hall - plum coloured velvet curtains and heavy wood panelling - but the usual damp, out-of-tune, upright piano here is a very splendid Bösendorfer with another Steinway on the stage. There is also a fine restaurant selling German sausage and Niertsteiners of high quality. (The British Council doesn't even have Theakston's Old Peculiar...)

One of the better policies of our Director at the College is that the staff should, where possible, actually do something. We all perform in our various ways at some time or another. I find this alarming (what can I do?) but also refreshing. We have - as it were - to put our money where our mouths are. I was asked to participate in this concert, but I have few scores here (none of them suitable) and I was asked so late I knew the time taken to get the scores from my publishers and the much-needed rehearsals would be risking too much on this, the first public airing of any of my music in Bangkok. I was content, on this occasion, to be a bystander.

My colleague Khun Surat Kemaleelakul (all names in Thailand are like that...) organised the event. He was trained in Chicago and thinks John Cage and Pierre Boulez are the cat's whiskers. Knowing this, I was anticipating (as one does at any contemporary music concert in Britain) 11 students and Surat's mum and dad to make up the audience. I didn't hurry to the Goethe Institut; I knew the concert wouldn't start on time. No event, speech, match or concert East of Suez is ever known to start on time. And there would be plenty of seats.

I had to stand at the back. Before 7.30 the place was packed. At 7.36 sharp (unheard of in Thailand; certain members of the audience were still downing the last drops of their Niersteiners in the restaurant below), Dr. Eri Nakagawa, our principle piano teacher, walked on to the stage in a svelte, black dress she may have had copied by the seamstress round the corner from a photograph of a Versace number. (We do that sort of thing in Thailand; you can still buy a pint of nails here...) She played with great conviction some short piano pieces by Khun Surat which I found charming if a little too derived from Webern. They made a perfect introduction to the more meatier fare which was to follow.

As Khun Surat had organised the concert it was understandable that a good many of the works on offer were by him. They got wilder. His last piece - straight out of those contemporary music concerts we few, we miserable few suffered in the Sixties - was called Parameter 1 for piano and double bass. It would be called that, wouldn't it? I don't need to give you a blow-by-blow account; Surat disappeared inside the Bösendorfer, the bass player dragged the bow slowly across the wrong side of the miked bridge - you know the scene. The last piece in the first half was by a student, Polwit Opanant. His piece, for solo alto saxophone and computer was called 3'44". It consisted of one note on the alto saxophone played intermittently and in various degrees of raucousness for - yes, you've guessed it - three minutes and 44 seconds. (I'm not sure what the computer did which could not have been done equally competently by his wristwatch.) Now there's originality! Polwit is starting at M.A. in composition next year. If he asks for me to be his supervisor, I shall soon knock the stuffing out of him! ("Write for me a Minuet in the style of Mozart." "I'm damned if I will!" "You'll be damned if you can't...")

Another part-time teacher at the college is a very tall, thin, shoulder-blade-length haired composer called Atibhop Pataradetpisan (all names in Thailand are like that...). He studied, rather unusually, in Tashkent, at the conservatory there. I had no idea that Uzbekistan was a centre for the propagation of contemporary music, but there we are... His main offering was Miniature for mezzo-soprano, piano and percussion. The marimba figured largely and I was waiting breathlessly for the appearance of an Mbira but none came. The poem, in Russian, was by the composer. As I have no Russian and have done the same thing in my first symphony I am not at liberty to pass comment. The mezzo-soprano was the composer's Uzbek girlfriend. She wants a job teaching singing at the college; but as she only speaks Uzbek and Russian ("I onterstant Ingliss very wull, but kennot speech eet") I await developments with interest. Atibhop Pataradetpisan's second piece was for guitar solo. It lurched from Albeniz to Webern in a matter of seconds; and later, when I talked to him, he admitted he had found it very difficult to write for guitar. I could tell.

The tenth item on the programme was by our jazz double bass teacher, Noppadol Tirataradol (all names in Thailand are like that...). In a line-up which included a piano, piccolo, tenor sax, bass sax and trombone, the composer played the TV screen. It ticked the seconds (but with some missed out and others clipped) for 12'30" - except it wasn't, if you see what I mean. Poor Wichai, one of my theory students and on the piccolo, was hopelessly out of his depth. He is a mature student with a family and is not used to turning his music upside down and blowing through the wrong end of his instrument. ("What did you think of it?" He asked me afterwards. "Crap." I said. "Ah..." He said noncommittally - very Thai. I don't think he knows what 'crap' is in English. Just as well...)

The eleventh and twelfth pieces were by a rather timid, elderly Thai teacher, Vijit Jitrangsan. who teaches Theory I. ("This is a chord..."). He shouldn't have done it. He writes gentle pieces for wind ensemble with titles like The Ship which meander through straits of the diatonic scales like Percy Grainger on a bad day. His two pieces suddenly brought into sharp relief the gulf which has opened up between contemporary composers and the rest of humankind. Khun Surat shouldn't have exposed him either; it was cruel. The audience shuffled and talked; a couple of mobile phones went off as if they knew their owners were happy to be diverted. We just longed for the whole embarrassing episode to end. Dr. Eri had come to join me at the back and, in an uncharacteristic, unguarded moment for a Japanese, grimaced at me. When this public flogging was over, we applauded weakly and Vijit bounced up and down, bowing from his seat in the auditorium. I hope he was pleased with the performance.

Geep is a jazz piano student and I don't teach him; but we have become good friends because he had always said hello to me in his naturally friendly way for weeks, even though I didn't know who he was. Out in the foyer I saw him. He came up to me and put his arm round me. "What I need now," he said "is a large beer and some good jazz. Coming?" "Lead on!" I exhaled. As we made our way out of the Goethe Institut I made nodding approvals to the various composers who were touting for warmth, approbation and affection from their admirers. They wouldn't let me go, and persisted with questions which I really didn't want to answer. "Let's get out of here" I whispered, and Geep grabbed my hand to pull me away. Two other students joined us and crammed themselves into the dickie seats of Geep's sports car. We wended along the narrow soi which leads from the Goethe Institut, out into Rama IV, up Wireless Road, across the top of Lumpini Park to Brown Sugar, a famed jazz café. With the aid of that splendid Asian institution, the street parking attendant, we parked easily near the café for the price of a tip. "I shan't stay long." I said to Geep as we approached the entrance. "I'm very tired." "Me too." He replied. "We had aural class at 8 o'clock this morning." As a boy Geep went to the American school; his English is impeccable if accented. The four of us sat at a table and ordered a pitcher of beer. The piano, electric bass, sax and drums were backing a young Thai singer who was very good. After the impenetrable music we had just heard, it was brought home to me just how much contemporary 'serious' music has lost by eschewing its primary function of communicating. Naturally on a Thursday the café was sparsely attended so we were welcomed through the mike by the bass guitarist. Four males sitting together were somewhat conspicuous and it was commented on: "No girls with you tonight, boys?" (I bristled at the epithet 'boy' but let it pass.) "Maybe later!" Geep called out. He turned to me and, as the music had started up, shouted in my ear by way of explanation "I used to bring a girl here. They know me." "I bet they do...!" I said quietly to myself.

I was content. We drank beer; we ate very spicy titbits; we talked and we occasionally made a request of the group: Love Walked In, I Got Rhythm ("Sorry we don't have that"), The man I love. It turned out Geep - much to my surprise - is as fond of the Gershwin/Cole Porter era as I am. I am always amazed when young jazz aficionados are as moved by these Paleolithic songs as my generation is. We stayed for a whole set but decided to call it a day when the group rested. The boys drove me home and Geep wanted to see inside my house - making the excuse he needed a pee. Thai people are endlessly curious ("How much do you get paid..."). What he expected to find there, I've no idea. He peed, looked round ("Nice house... really nice house... yeah...") and left.

***

Since the beginning of this semester (what an ugly word!) I have been training the University Chorus; a grand title for the music students who are left who don't play in the Symphonic Wind Band or the Thai Orchestra. Thus I am landed with pianists, guitarists, composers, string players, percussionists and singers. It is compulsory; never a good start where music and students are combined. I had been warned that it was awful: they couldn't sing in tune, they couldn't sing in time and they couldn't be bothered to turn up. The last concert, Schubert's Mass in G, had been a disaster. But they hadn't reckoned on the former conductor of the Sutton and Bignor Singers and the founder of the Grimsby Bach Choir; both of which august and successful bodies (both still flourish) were open to all comers; none was turned away. Even Nick Brimblecombe, who couldn't sing The National Anthem in tune, was found a small niche amongst the tenors of the Sutton and Bignor Singers (but he was politely told to sing sotto voce). This is a piece of cake! I thought. I've actually got people who are 'majoring' (another ugly nonsense word) in singing. But I was cautious: I decided to test the waters with a nice simple baroque cantata: Purcell's Come Ye Sons of Art. We even had a countertenor! Marvellous! The form is: we rehearse throughout the term and give a public concert at the end. The first rehearsal, 14 weeks ago, was just as I had been warned. I hadn't actually stood in front of a choir for over ten years and was alarmed at the work I needed to do if my reputation as a choirtrainer was to be preserved intact. They were just dreadful. I summoned up from the nether recesses of my feeble brain all the tricks I had learned from my adolescent days with John Bertalot at S. Matthew's and the countless rehearsals I had taken since. I cajoled, I shouted, I whined, I played the fool, I stormed out, I tore up copies in front of them, I laughed, I beamed and I growled. Gradually they started to see the point. Jazz players like Geep suddenly became interested, prima donnas who know everything there is to know about singing gradually started to listen to those around them, guitarists who had a touch of the Nick Brimblecombes began to sing in tune. You must remember these are Thais who don't even know much Roman script, let alone how to pronounce 'innocent revels'. ("Ajarn Lobert! Please: What is 'Levens'?" "It's 'rrrrevells'. Well... a sort of party." "...and 'illocent'?" "Ah... yes well... it's when someone doesn't know very much." "Oh! You mean 'Illocent Levens' is a sort of stupid party?" "Well...yersss... something like that. Bar 56 ladies and gentlemen, please: bar 56...")

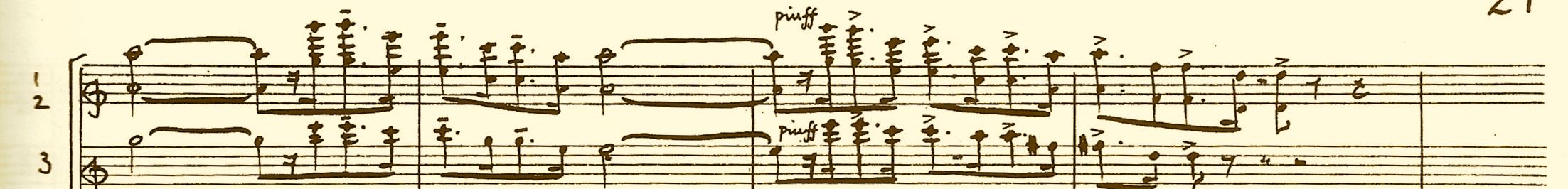

I was also determined to perform this Purcell Ode with an orchestra (the Schubert Mass had been done with piano). I knew we would never get the parts out of the publishers Schotts and sent to Bangkok in time; in any case, the director would have had a fit if he saw the ludicrously expensive charges for hiring orchestral material. The music industry, as far as I can tell, is perhaps the last dinosaur that has not understood the fact that if you sell things cheaply people tend to buy more of them whether they need them or not. So I set about doing my own edition and writing out a harpsichord continuo part. No keyboard player has any experience of figured bass playing here. On my computer I wrote out all 574 bars of the full score of Come Ye Sons of Art and a new continuo part. We don't have a harpsichord either, so a Clavinova would have to do. We don't even have a hall yet so I decided to do it in what will become the canteen of our new, splendid college of music - builders, builders' rubble and all. I had no idea when I made all these decisions what eventual horrors I was to let myself in for.

Over the weeks the choir got better and better and the soloists got worse and worse. the countertenor was a nightmare of nerves. A small weed whose nickname was appropriately 'Titti', he never came to a rehearsal, or came a day early, or came a day late. Eventually I had to abandon him and give all but the opening eponymous number to other singers. Even that he never got right. Other soloists got very grand and wanted transpositions or wanted to swap solos with their friends. It was a nightmare of mammoth proportions. It has long been my belief that, if you want trouble in a musical performance, include singers and trumpeters. So it proved here: neither of the two trumpeters turned up for the first rehearsal, they were an hour late for the second and forgot to bring a trumpet in D to the performance so played the difficult bits an octave lower. Four days before the performance the double bass pulled out to go play jazz, and one of the grandee soprano soloists (who has nothing to be grand about) announced she couldn't possibly sing Bid The Virtues, it was far too long and her voice would not take the strain. I've struck her off my list... On the day of the performance (last Friday) the gofers forgot to bring any chairs. What I forgot was the wind. I don't mean the wind players. The wind. The area we were to perform in is open at both sides of the building. Above it are high-tec, curving galleries with steel handrails (still wrapped in their protective plastic) where the audience would, I imagined, promenade. It was actually a stunning location and the acoustics in this brand new, still empty building were wonderful. But I forgot the wind. When it is a perfect day in Bangkok - and it was a perfect, cloudless, cool day (only 32 degrees C.) - there is a slight breeze coming down the country from the snows of Southern China. This cooling zephyr is much welcomed. But this zephyr got funnelled into one opening of the putative canteen on the College of Music, Mahidol University, mutated into a roaring gale as it roared round the galleries, then rushed out screaming on the other side. We didn't have any pegs. Violinists rushed off to retrieve floating pages, cellists grappled with ground basses and flying music, oboists let out a shriek as one hand left the instrument to stop a page from billowing off into the Gulf of Thailand. I conducted the final rehearsal with one hand, and occasionally from memory when I forgot to hold it down, and a kindly tenor brought back my score.

In the end it was a great success. Even Titti got his solo more-or-less right; but there was a heart-stopping moment when I looked round to see if he was ready to sing and he was nowhere to be seen. I spotted him at the back still warming up. I signalled frantically that he should be at the front. He started his solo still running the last three steps. The Prima Donnas got Sound the Trumpet more or less together, Imola, the Hungarian singing teacher, stood in splendidly for Titti in Strike the Viol (or "Strake Ze Wiol" as it turned out...), I had a guitar as continuo for Bid the Virtues and he played hauntingly; even tall, gangling Prem, who has never been known to turn up for anything, was there and ready to sing The Day that Such a Blessing Gave. But the highlight for me was Wongsathorn Narumit (all names in Thailand are like that...), a first year baritone, who suddenly blossomed and - the metal installation sculpture in his mouth to re-allign his teeth notwithstanding - gave a commanding performance in These are the sacred Charms and the final chorus. I was glad his mum had clambered over the builder's rubble to get there to hear him.

Ah! My darlings the chorus! They came up trumps and actually sang in time and in tune. They even remembered to sing 'revels'. They had learned Purcell's music too quickly, so - fearing they would get bored with more rehearsal and their performance would go over the hill - a couple of weeks back I introduced Stanford's Blue Bird as an encore. For those who know it and know of its war-horse status, I can't tell you the pleasure it gave me to introduce this little gem to a body of singers who had never even heard of Stanford - let alone his blue bird. Their little faces literally lit up every time we sang it; and one girl with bleach-blond hair, a skirt so short it left nothing to the imagination, cobalt eye-shadow and six inch high sandals burst into tears after a particularly memorable try-out. I had the soprano solo, Ragthaitip Phasuk (all names in Thailand...), stand above us on a high gallery. The effect would have been even more magical were it not for the distant but distinct pneumatic drill which had been a constant leitmotiv throughout the entire performance. The Director was there. If I've still got a job at the end of the month, I'll let you know.

***

The performance was in the afternoon and I had been given two VIP tickets - row B - to the first performance that evening of what was billed as the first Thai opera by a Thai composer. I was exhausted after the tensions of putting on Come Ye Sons of Art and didn't really want to go; but I knew a number of friends were going - it was the social event of the season and had been puffed up in the press for weeks - so I felt it incumbent upon me to use these generously given tickets. I rang Jamorn to see if he was going from his home round the corner. He was, so we arranged to go together. I arrived at his house breathless and a little late only to find J. just beginning his shower. This is Thailand. A pupil of his was coming too so I gave her my extra ticket. She bowed and scraped with immoderate gratitude. The traffic, when we finally got going in Jamorn's car, was appalling and we inched our way towards Soon Wattanatam - the huge cultural complex on Ratchadapisek Road. As we got closer and slower we were aware of policemen everywhere. Traffic in all directions was brought to a complete standstill. This is always a sign that Royalty is on its way. And so it was. A mobile phone call from Jamorn's mum who was waiting perplexed at the theatre informed us that the King's granddaughter was on her way to the opera. "All this just for his granddaughter!" I said. "You wait!" said Jamorn.

We finally made it 20 minutes late; but this is Thailand and the performance was not even imminently about to begin. After I had viewed the now empty, stretched, gold-plated Rolls-Royce and the honour guard of young Naval officers in full dress white uniforms, I ambled through the foyer and sauntered down to row B (Jamorn, his friend and his mum were up in the Gods) to find myself surrounded by generals and their wives. It is a little known fact that Thailand has more generals per capita of service personnel than any other army in the world. They sat in the front rows, paunchy, puff-faced and looking very mean. Their wives gave cold stares through diamante spectacles, and gave the impression they thought it was the most natural thing in the world to beat one's maid.

After the usual speeches (the Thai middle classes can do nothing until someone has made a speech), a rendition of the synopsis in Thai and in English and the National Anthem - de rigeur even at Thai boxing matches and string quartet recitals - the lights went down and Madana, the first ever Thai opera (in English...?) began. And the moment it began on an orchestral chord filched straight out of Richard Strauss I knew I had made a mistake in coming. My dears, it was dire. The story had originally been written by King Rama VI - the only known overtly gay monarch this side of Louis XIV - based loosely on an old Ramayana legend. If it were not for the surtitles I would have been blissfully ignorant the libretto was of the "the moon is pale tonight, O beloved one, my King and Lord" type. (Someone had to sing that mellifluous word 'futile' more than once.) The singers couldn't act, the dancers fell over, the chorus was straight out of the Haslemere Amateur Operatic Society, and the principles (two Americans) were hopelessly out of their heights. The sets were fussy and the costumes had been designed by someone who thought they knew what Vivienne Westwood was like. But it was the music which made me groan outwardly (but quietly for fear of the generals). Had Strauss decided to write a pastiche of Verdi he would have come up with this. There was not one ounce of originality in any single bar. I was aghast. All this money! All this effort! All these people! And for what? They had far better put their investments into Rosenkavalier; the story was much the same.

The first act was short. Oh blessed relief! And I went outside to find Jamorn and Piak. "I'm going home." I said. "This is not my kind of thing." They agreed it was pretty awful but begged me to stay to see how it ends. "I know how it ends!" I groaned. "Come and sit with us. There are plenty of spare seats." And they grabbed both my hands and forcibly led me up to the circle. I nearly succumbed, but half way up I wrested myself from their clutches. "No! No! I can't! I simply can't bear any more music! I'm tired and this is the last thing in the world I want to do right now." They relented and I escaped past the naval officers who were now pressing people to buy paper roses in aid of a hospital charity. I fairly ran past the stretched Rolls-Royce, out past the maddening crowd and into Ratchadapisek. I flopped into a passing taxi. The handsome driver flipped on a cassette of loud, Thai pop music. For once it almost sounded acceptable. "Hello." He said smiling. "Where you flom? Where you wanna go? You wan nice girl? Nice boy?"

Home. Just home. And bed.